Seasickness, in fact any kind of motion sickness, is something I’ve been plagued by all my life. Long, vomity car rides; being miserable and nauseous on every boat I’d ever been on up until this point; even park swings as an adult were rides of gastronomical danger (adults can still go on park swings, goddamnit – they need to be built to withstand the weight of fat kids). People always ask me – if that’s the case, what on Earth possessed you to buy a boat? In what reality did you see this as a lifestyle you’d enjoy? The thing is, I just (and always have) love boats, and I have a sort of optimistic (private-school induced) confidence that nothing is a barrier to me.

Seasickness Basics

The phenomenon is caused by a range of factors, the number one being an inner-ear imbalance. Your body senses a bunch of movements which don’t necessarily correlate with what your eye sees, and your brain panics and thinks something is wrong. Some theories say this can cause your brain to think your body has ingested something poisonous, and is trying to get you to purge yourself. At any rate you get sweaty, nauseous, dizzy, and in general feel like you’re going to die. It can be very debilitating on a boat, and induce dangerous behaviour (like jumping overboard). It seems to be something that some people get more than others, either due to genetic or psychological factors. Everyone in my family gets somewhat sicky, although my Mum claims that now she’s losing her hearing, it’s not such a big problem any more. Your state of fatigue (including how much you’ve eaten) and stress also play an important part. General advice to avoid it involve looking at the horizon, getting fresh air, chewing gum, or having something gingery.

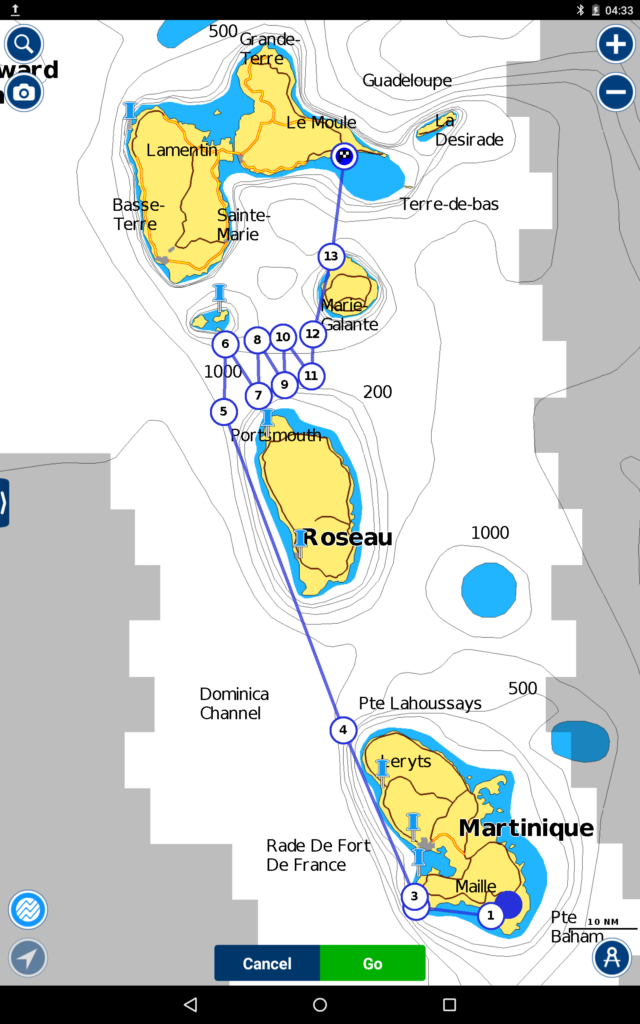

So anyway, by Easter 2017 my time in Martinique was nearly up for that season, and because I didn’t yet have local boat friends to turn to, my mentor (who I call the Zen Master, for reasons that will become apparent), had come over from Guadeloupe to help me to deliver Anne Bonny there for hurricane season. This meant I had someone who could air the boat from time to time to prevent mould, and tie her up appropriately should Big Weather arrive. Zen Master was a retired optician who now practised Janzu underwater massage – a spiritual healing process that involves some kind of synchronised drowning experience. He was not only an excellent sailor, but also possessed Great Wisdom. This delivery seemed really simple. A nice easy-going sail with an able and experienced captain, and a fun friend as extra Crew. Just a couple of days’ journey – Gwada isn’t that far away. Anyway, to be melodramatic, it turned into a traumatic seasickness-laced nightmare from hell, that would shake me to the core, sweeping any vague foundation of confidence I might have fostered clean away. Seasickness is merciless, and if you’re the captain (which I really wanted to be able to be, at some point), potentially deadly. But maybe there’s a way around it, even if you’re a chronic sufferer like me.

Despite previously mentioned engine troubles, Zen Master and myself set off from Marin without drama and in lovely conditions. We were to anchor at Anses d’Arlet to meet the Crew, and proceed to Guadeloupe from there. It was amazing to be sailing my own boat, and Zen Master got to work giving me some valuable lessons in reefing the mainsail and when it was appropriate to do so (ie whenever someone on the boat so much as thinks the phrase ‘maybe we should reef’. In fact in this region, you’re often best to leave with at least one reef in, and see if you need to take it out later). We were chilled out. We even saw whales. However, complications came later on when we needed the engine and found that it sort of died after about 20 minutes of use. A gearbox somethingorother. I didn’t really take in the severity of the situation at that moment, because although Zen Master seemed alarmed, he wasn’t thrown. I hoped these were just weird gremlins that were going to go away. (By themselves…? Because that’s how boating works, right?)

We didn’t have autopilot, so took turns at the tiller – although Zen Master did most of that work. By the time night fell as we were passing Dominica, he was pretty tired. There’s not much wind passing Dominica as the mountains block it out, so there was a long game of start the motor, enjoy its gentle rattle and chug for about half an hour, and then listen to it peter out. Then the rain started coming, and at this point all my sense of geography runs out because there was just blackness and waves, and fatigue, and an increasing level of nausea both for me and the Crew. We took it in turns to sleep below, as the bateau lurched and threw me into a sort of hallucinatory stupor of misery. I honestly thought I was going to be OK, but when I reached for the bucket for that first time, it was game over. The fridge had already been flung from its cubby hole and was littering its contents all over a cabin already strewn with broken things. I clung to the bunk, strange little voices whispering in my ear, unable to clean any of the puke that had not made it into the bucket. At some point I pulled myself together enough to stagger up the companionway ladder to empty the bucket over the side. And bless the Crew, she tried to take it from me (shivering on the cockpit bench), but she ended up spilling it all over her legs instead.

However dreadful I felt, my time in the warm bunk was up and I was forced to swap places with the Crew. Zen Master made me promise to sit there and stay awake, but it was impossible. The sea heaved in the blackness and pouring rain around me, and I couldn’t keep my eyes open. But he couldn’t do this alone all night. I don’t even remember how he did it or when he rested, but I just clung on there with tears in my eyes, vomiting away in my bucket, praying for daylight and an end to the torture.

Dawn arrived at some point and I was devastated to see we were nowhere near our destination. We were going to stop at Marie Galante for a break, but something due to the wind direction and lack of motor had meant we’d been tacking back and forth most of the night and still had a lot of rainy misery to go. When we finally anchored I cowered in the cockpit and wrote this in my journal:

Everything on my boat is wet and everything is wrong with my boat. We’re a couple of days into the delivery to Guadeloupe. The first day was quite nice, it just became apparent that the gearbox is fucked. Now we’ve just got in from 30 hours sailing hell and a rainstorm has showed me every single one of my deck fittings leaks. It’s been quite demoralising. Not just finding out that so many of my things don’t work/leak (the leaks are the killer), but that a long sailing trip was torture. I simply can’t function when I’m seasick and I couldn’t stay awake during night passages. My body sends me to sleep. The leaks are still the worst. Everything feels horrible and they’re the reason it smells so bad. Plus the vomit I suppose. Also demoralised about my skipper skills, but of course there’s still a lot I don’t know.

(I was really down about the leaks.)

We spent a day at anchor to recover and visit the island a bit, before preparing the final leg across the channel to our intended port. I was deeply ashamed of the way I’d handled the night passage, because I’d been truly pathetic and unable to do anything about it. I asked Zen Master how I would be able to defeat my seasickness problem. I used these exact words and he immediately picked me up on it. He told me kindly that my mistake is I treat it as though it’s a battle. You can’t fight seasickness. You have to accept it and go with the situation. He noted that I am clearly a person who needs to control. He’d hit the nail on the head there, because I’m a natural control freak and it’s something I spend a lot of time trying to get over. He qualified his statement by assuring me that it wasn’t necessarily my value, but a value I’ve probably learnt. Maybe I learnt it from my mother, and maybe she learnt it from her mother. Maybe something happened in my grandmother’s life where she needed to be in control to avert danger, and she’s passed that on emotionally and with physical effects. So maybe this need to control isn’t my own value, or part of my own story. I should work to find my own story and let go of whatever this burden is that isn’t really mine. Words to that effect.

He was using the mother/grandmother thing as an example to make me explore the roots of my issue, but it hit home immediately. Later I was relating the episode to Mum because I know she’s also struggled with motion sickness, and (I hope she won’t mind me saying) has a naturally controlling nature. She just looked at me and said, that’s exactly it. I wrote way back at the start that I’d come on this adventure partly to discover a grandmother I never knew – in a way to fill in the gaps in my own identity. When I explained what Zen Master had said about my controlling nature not being part of my own story, but simply a hangover from what my grandmother went through, Mum told me a bit more about what it was that Joyce had lived.

Joyce Nugent had come to live in Antigua when she was four, but her family had been here since the 1700s. She’d married my grandfather when she was quite young, and when the second world war had broken out, my grandfather had joined the navy. She’d been left alone, pregnant, and looking after a toddler. Her father had recently died and her mother soon moved to another island to be near her youngest brother. Her favourite brother also died in action in 1940. Her two sisters were nurses so they were also busy. She had to cope on her own. By the end of the war she had three boys, one of whom was deaf, and because of this my grandfather couldn’t go back to his job in Antigua since there were no deaf schools there. He either had a nervous breakdown or became depressed, and she had to cope alone again.

Mum also noted that my great grandmother had been in a similar situation. They’d moved back out to Antigua because her husband (my great grandfather) was too ill to move to England after retiring from government service in Nigeria. He got progressively worse until he died approximately seventeen years later. So my great grandmother also had to cope with bringing up a family without proper male support. Both had husbands who were alive but not able to be the proper heads of their households, which was expected in those days. These women had lived in chaotic times with a load of kids and no support, just trying to hold it all together. No wonder they were stressed-out control freaks.

It can be easy to dismiss relating things that happened in someone else’s past to your current situation as a bunch of spiritual waffliness; but when tension, control and stress develop as personality traits, these personality traits are unintentionally passed on to the next generation. (Don’t forget Philip Larkin’s immortal lines, they fuck you up, your mum and dad. They may not mean to, but they do.) Anyway the point of this little sidebar, as well as returning to the context of this writing project as a whole, is to illustrate some of the other influencing factors on seasickness and how you can do something about it, once you understand why it’s happening (and why ‘watch the horizon and suck a mint’ might not cut it for some people).

You have to let go of trying to control your environment (even if it’s unconscious), because you just can’t. Someone had once commented that it looked like I was afraid of the wind. I’d been explaining a silly phobia of kites that nonetheless made me still very unconfident with my sails. I realised he was right. The sea and the waves don’t faze me at all – but the wind is terrifying because it’s unpredictable and I cannot possibly hope to control it. At sea, when you stop trying to control everything around you and just embrace the situation, your tension fades. You were trying to do too many things at once, silly. And on top of that, what you were trying to do was impossible. No wonder your body couldn’t cope and your inner ear made you sick.

Zen Master explained about a technique of breathing, being present in the moment, and just letting everything go. When you start to feel bad, breathing can be very helpful. It’s also helpful to remember that you can’t force anything on a boat – both physically and in terms of attitude (so don’t try and force yourself to be well). If you’re forcing a rope, something risks breaking. If you’re finding yourself needing to force something, you’re best to change the method so that it doesn’t need a lot of strength. Fundamentally your attitude is the important thing here. When people join the boat I work on and are anxious about feeling ill, I normally advise them that the fear and stress can often be part of the problem. The best thing is to accept that maybe you will become seasick, and that it’s ok because you’ll have a method to deal with it. My method is to lie down and close my eyes for 10 minutes or so. I find if I’m at the helm, or in a position of responsibility whereby I simply cannot afford to be sick, I somehow step up to the mark and keep my stomach. But when I’m sailing I find people talking to me too much of a distraction. I need all my focus to be one with my environment, accept the movement of the waves and release my tensions.

This idea of using principles of Zen when sailing genuinely changed my life, especially now as I pursue a career at sea. With the fear of getting sick now calmed, I focus on keeping myself rested and fed to avoid fatigue, and appreciate the majesty of the ocean (whatever its state) as I get in sync with its movements. And look at the damned horizon. I still get nauseous sometimes, but that’s OK.

Yesterday was the last leg from Marie Galante to St. Francois. We sailed off the anchor, not trusting the engine, and the Crew decided she would head to the mainland by ferry. Screw Anne Bonny, she was done with us. It took 8 hours rather than 4, but the weather was sunny at last and I took the helm for most of it. It was a kind of relaxing meditation. I learned a lot about how the wind worked and how to gain speed. Normally when the boat heels I fight against it and try to get us straight again, but I realised that this loses you speed, and speed can be important on a long crossing when the crew are getting tired. I tried the Zen Master approach and went with the lift, relaxing and letting the boat do what it needed to do. It worked! We couldn’t trust the engine so we did some complex manoeuvres to enter the marina under sail (once again, so lucky to have this skilled sailor there to help me). And then suddenly the bateau was tied up in its new home. We’d made it!

All the Zen stuff sounds very similar to the Mindfulness I have been reading about. My boss calls it “Going with the Flow”. I guess a lot of people have similar but slightly different methods of letting go of control and embracing what is going on around them.