I was pretending not to be nervous as I flagged down my bus, my takeaway canteen lunch in hand. I’ve always had a weird self-consciousness in new places – like I don’t want to show my vulnerability. I want to seem like everything I do is completely old hat, done hundreds of times before, because I fit in. Which is stupid, because in this instance, I was clearly a foreigner. But I’d got used to feeling like Martinique was my home, and that I could move about easily and (as I liked to think it) gracefully. As graceful as any classic sticking-out sore thumb could be, anyway. But this place was nothing like home. I repeated the mantra ‘think like the Poet’ in my head, trying to relax and wondering if I had the guts to make polite conversation with the assortment of school girls and old folks on the bus. He would have used his charms to open one of them up like a clam, and found out the name of their neighbour’s daughter who had a shop in town he should definitely call on (and he probably would). I just managed a couple of ‘wow, there’s a lot of mud’ type comments, to which the school girl was polite enough not to roll her eyes too obviously.

Anyway, at least I was off my boat and on my way to St John’s for the first round of my Nugent hunt. The easiest project first: the cathedral where my grandparents had been married. Alighting from the bus, I had it in my head to go find a quiet spot where I could eat my lunch undisturbed. This proved to be naïve. I could feel the sets of eyes burning into the back of my neck as soon as I emerged, blinking in the dazzling sun. A young monsieur with long dreadlocks and a bag of mangoes stopped me for a ‘chat’. His opening line was to the tune of ‘beautiful girl I want to spend time with you’. I had my invisibility ring (my old wedding ring) on, so felt confident that I could handle this. ‘Very flattering, but I’m married’, I said cheerfully, flashing my ring which I was struggling to keep on my finger, as divorce had entailed quite a lot of weight-loss. I continued to walk, scouting for somewhere to eat and regretting not having just got a wrap I could walk-and-munch. Monsieur followed. ‘What are you up to, beautiful? You going to talk with me?’ I told him I wanted to eat my lunch (now cold), and visit the cathedral (because I suppose he could at least tell me where it was, and then I won’t have just run away from the encounter, to be lost somewhere else and repeat the same conversation down the road).

I don’t really know how it happened, but half out of awkward British politeness, half some of what I thought of as the Poet’s lingering spirit of adventure and openness to new encounters, I submitted to being led through this open-air shopping centre, to a shoe store he said belonged to his cousin. I had the vague understanding that this was his solution to my ‘where shall I eat lunch?’ problem. I said fine, I would eat with him, but after that I really had to be off. Timothy (or Shotta) – his introduction had been a bit mangled – had some small girl produce a stool for me and waved his hand for me to sit down. I did so, giving the girl and the security guard who was hanging about outside, an awkward smile each. Shotta (or Timothy), in the meantime disappeared to hunt me down a cigarette and left me to try and eat, with a small audience who were probably as baffled as I was. ‘It’s very good’ I indicated my polystyrene dish, for want of conversation ideas. ‘I don’t know much about Antiguan food’. Nobody said anything. I started wondering if now was a good time to run away, and if he’d notice.

He returned what seemed like an agonising eternity later, proudly flourishing the cigarette, which I accepted meekly. He informed me he had to catch the ferry to Barbuda, but he was going to show it to me first, before I went to the cathedral. At any rate he would happily miss the ferry for me, if I wanted him to. I told him I couldn’t do that – he had to see his mother, bring her the mangoes, etc etc. He paraded me past a bunch of leering lads, who went hiss hiss at me. ‘Have you lost your cat?’ I plagiarised a joke from one of my Martinique friends, and everybody laughed, so that was good. ‘It’s my gyal’ he snarled back at them. The women gave me dirty looks. I sighed. I’d channelled the Poet enough to befriend a Rasta, but sadly not one of his Secrets of the Universe Rastas like in Dominica. Random encounters are not as fun, it turns out, when you’re a lone woman.

He propelled me through the streets, chattering away. (The upside of all of this was, that he was sort of my protector. Normally you’d have to fend off all the guys who tried to have a ‘chat’, but since I was already claimed, everyone else stayed away.) He was very keen to impress upon me that he was a Nice Guy (not a Badman), and that I was beautiful, and that he’d been to prison for murder (but only to help out a friend). He didn’t do it, the friend did. He was not a Badman. I was beautiful. How many kids did I have? None? That’s a poor effort. He had nine. He left his mangoes at the ferry, passing me a handful from the sack with a grin. ‘That’s very kind, thank you.’

The cathedral (which I dutifully photographed for posterity’s sake) was all shiny and fresh wood inside. A plaque said it had been completely rebuilt, so wasn’t doing much for evoking past ghosts. Timothy (or Shotta) wandered up to the lectern and opened the heavy Bible. He flashed another of his big grins and proceeded to try and read for me. I pretended to clap and be impressed, but after a few phrases his words stumbled, and he pulled away, embarrassed, muttering that reading wasn’t really his thing. A member of the cathedral staff hovered nervously nearby as Shotta rambled around the pews, poking and admiring as vocally as he could. His phone rang and he swore loudly.

‘Ferry leaving’, he told me. I pretended to be disappointed, and ushered him out of the doors, shooting the employee an apologetic glance. He became a bit frantic at this point, trying to at least get my number so we could ‘stay in touch’. I didn’t have a pen, and neither did he. Eventually he took a stone and scratched his number into the paving, before scampering off down the hill. Dutifully, I took a photo of it, and breathed a sigh of relief. I really wanted to be alone with my ghosts. I snapped a few pictures of the outside of the cathedral and tried to associate it with the wedding photo I’d seen.

1934

Just before I left Antigua to go to school in England, I was sent to collect 2/- for a raffle, from my sister’s new boyfriend. I did not get that 2/-. 5 years later I made him pay the penalty, I married him.

Joyce Robertson (née Nugent) ‘Some of my travels’

Next on my hitlist was the museum, which someone had told me about, and which I hoped might give me some depth or insight or something, about the historical and social context of the island. I intended to ask about the sugar factory my grandfather had worked in, and where I might find it. The museum inhabited one largish room, and had a few displays of bits n pieces but probably not the goldmine of information I was hoping for. I knew the sugar factory was called Gunthorpe’s, but the sign (and the kind person behind the desk) insisted Guntropes. I was just settling in to get my money’s worth and read every single plaque in the room, when the door clattered open and a familiar face bounced in.

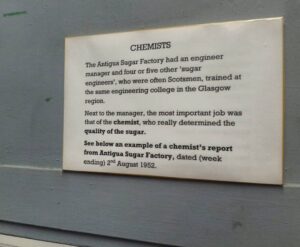

‘Missed the ferry, beautiful,’ Shotta/Timothy informed me with a shrug. ‘But it’s no problem, it means I got to spend more time with you.’ He was delighted, and since I hadn’t told him about my plans to go to the museum, he’d either followed me or just asked people on the street where the white girl had got to. There were a few colonial weapons on display in the hands of papier-mâché figurines. He lifted one up, showing off. I glanced at the lady behind the desk, and decided to stop caring. Shotta and I were in this for the rest of the day, I realised. There was no escaping my escort. I continued to read the plaques, muttering about the damned colonialists. He didn’t bother to pretend to read, and restlessly prodded the artefacts. I beckoned him over when I found a display in the back corner that actually meant something to me. So far there hadn’t been any mention of any Nugents (I suppose they weren’t that important a family), but there was a tiny mention of the sugar engineers who came to work on the island, generally recruited from the same engineering college in Glasgow. That was it! My first tangible thread to the story of my grandparents. I was given a bus timetable and instructions for how to get to ‘Guntropes’, and felt like I’d used up all my exploratory energy for the day. I told Timmy that I needed to go home now.

He warmed to his tour guide role, and showed me all the highlights of the town on the way to the bus station. He was mostly performing to the pals of his that we passed, but by now I was ok with this whole bizarre situation. He pointed me to the correct bus, took my number, told me I was beautiful again, and (much to my surprise) disappeared off into the busy street. I checked the bus really was going where I wanted to be, and collapsed into a seat on the back row, drained. I never felt particularly unsafe with my guide, but it had all wrong-footed me. He seemed like he was being genuinely friendly, but my suspicious side-thoughts wondered – what does he really want out of this situation? That’s a cultural space I’m still trying to navigate.

Despite the tumbleweed of the Jolly Harbour anchorage and marina, I’d decided that I wasn’t going to be lonely now I was finally in Antigua. I risked stalkers and murder, and declared my arrival to the island’s cruisers’ Facebook group. I was anchored to the lefthand side of the channel, I told them; I was aboard Anne Bonny, and I was alone. Who would be my friend? To my surprise, several people raised their digital hands. One came to visit in his dinghy (because I’d practically given my lat/long – luckily he was neither creep nor murderer), invited me for tea with his wife and kids, and helped me get my ripped mainsail ashore to be picked up by the sailmaker. I also had a message from Erika, manager of an Italian restaurant that was miraculously still open (she doesn’t have a nickname because she’s already mentioned in another post). So that was where I headed next, after my jaunt into town. She was gorgeous and glamorous and knew her shit about boats. We chatted until she had to get ready for evening service, and told me to come back again for coffee the next morning. After that in this hectic social flurry, I was invited to sundowners with this retired Yacht Club type in one of those houses with the space to park your boat outside. We chatted into the evening, with deep and interesting discussion, which led to dinner and a joint. I was beginning to feel that everyone here was lovely. People were just being so nice to me. But then he suggested we sleep together, which felt so age-inappropriate and uncomfortable, I practically leapt back into my kayak and paddled away into the night.

I don’t know why I agreed to go back the next morning. He’d lured me over with a shower and the offer of laundry, by way of apology I suppose. I felt supremely awkward, but hadn’t washed properly in ages and a hot free-flowing shower in a room that didn’t move was a real luxury. Plus doing laundry in a machine rather that a bucket, where you might stand an outside chance of getting at least some of the dirt out – this was an opportunity not to be sniffed at. Yacht Club knew what it was a like to be a cruiser. And he threw in some internet access and the chance to fill some water bottles. The journey there was a hard slog in the kayak against wind and current, with nonstop rain. As soon as my laundry was done, I told him I was due at Erika’s for coffee, and made a quick getaway. ‘Erika’ he snarled. He did not approve of Erika, it seemed. ‘Be careful of her’, he warned me. I thanked him awkwardly for all his kindness, and piled my laundry and water and newly-scrubbed self into my kayak, where I proceeded to get a soggy bottom and drenched from the rain, negating all of my morning’s efforts. Erika’s house was a couple of canal-blocks away, and I was told to recognise it by the lovely baby-blue boat parked in the slip.

I loved old Annie B of course, but I was guilty of a bit of a wandering eye, and I had an immediate crush on this boat. Erika and her husband were in the middle of some heated discussions with some builders, but she helped me tie up and graciously gave me a tour of her boat. They’d sailed it across the Atlantic and lost control of their rudder in the middle of the ocean, she recounted. Rebuilding the steering on passage was a tough job, especially having to use a tiller with such a heavy boat, but when a passing cargo ship called to ask if they were OK, they proudly said they were doing fine. She told me that the very fact that this ship out there in the middle of nowhere had been watching out for them made her feel a whole lot safer. When they finally arrived on the other side of the pond, they made their way to St Maarten, where they were engulfed by Hurricane Irma. (I recounted their survival of that storm in this post.) They’d been working on her repairs ever since, preparing to leave for adventures elsewhere as soon as they finished and could find someone to take over the restaurant.

Erika made me a coffee in her building-site of a front room/garage, looking out over the canal. I told her about my encounter with Mr Yacht Club. ‘Him!’ She rolled her eyes. ‘Better stay away from him.’ He was a notorious creep, apparently. Maybe creep wasn’t quite the word, as he was always pretty smooth about it. He had a Reputation, let’s say. For pursuing a lot of women much younger or way out of his league. Later I learned there was a bit of a Team Erika vs Team Yacht Club (which is a term I’m using to encompass all of the other slightly prissy British we-still-own-this-place types) going on. I’m glad I chose Team Erika.

It would have been so simple just to give in to my laziness and hang out in this easy marina enclave I’d found myself in, with my new friends at the Italian restaurant and in the anchorage (Erika had also introduced me to some of my now all-time favourite people, William and Mary, on a fancy boat in the marina), but I was supposed to be on a mission. I ratcheted up the difficulty level one notch and resolved to take the two buses I would need to find Gunthorpe’s, the sugar factory my grandfather had came to Antigua to work as an engineer in. I moved through town with a bit more determination today, without much harassment, and only got a little bit lost looking for the second bus station. A street vendor (through some kind of miscommunication) sold me two lunches when all I had really been after was directions, but I didn’t risk stopping anywhere to eat them. I did not have a Shotta or even a Timothy today.

The bus dropped me outside the factory, which was big, ruined and deserted. It looked like there was normally a museum there, but it was all closed up. There didn’t seem to be anyone about, so I opted for a bit of casual trespassing. Flip-flops do not make great trespassing garb, especially when there’s broken glass and aggressive weeds everywhere. My bare mud-flecked legs felt exposed to the teeth of the snarly looking dogs that zoomed out of a nearby car dealership. This dealership seemed to have organically spilled into the ruins of the factory, in the same way the living landscape had shot out its tendrils to consume the old building. Inside, there were just piles and piles of dead tyres. I closed my eyes and tried to imagine this as a working factory in the 30s, now that mills had been replaced by steam engines.

Aside from the activity going on at Betty’s Hope, this was pretty much the last of the sugar processing that took place in Antigua. The internet has been pretty unforthcoming with regards to further details about the factory (curses upon the closed museum; my post would seem a whole lot less ignorant if I’d arrived during high season and had had some plaques to read). As far as I can tell, it opened in 1904 or 1905 and was known as the Antigua Sugar Factory, and closed in the 1970s (but who knows how reliable the scanty internet sources are…). Cousin Nick writes on his website: ‘Mechanisation and trade unionism demonstrated what estate owners and managers had been slow to accept: that sugar production was not viable in Antigua once estates started to pay their workers living wages. From that time the sugar industry went into decline. Sugar is no longer grown in Antigua.’

The Caribbean’s relationship with sugar is (hahaha) bittersweet. In Martinique the sugar cane harvest is a big part of the seasonal calendar of the island, and the rum is celebrated as some of the best in the world. The distilleries are often still owned by the old families and are big sources of local economic power. In islands where it’s still grown, sugar cane might be a valid part of an island’s agricultural output now, but we must never forget its historic role. Sugar is EVERYTHING in this complex and bloody story of colonialism, slavery and the Caribbean. The Caribbean colonies were so important because there had started to be a demand in Europe for sugar, and there were only certain conditions under which the canes could grow. That growing it was so hard, the heat so high, and malaria another imported factor; African slaves rather than European indentured servants became a more (vomit) ‘cost-effective’ way of farming the crop. One of the principle and driving reasons that so many people were abducted and enslaved from Africa, and why so many of the current inhabitants on these islands trace their very recent ancestry to enslaved people, was because of the sweet tooth of Europe. Carrie Gibson in her book Empire’s Crossroads – A new history of the Caribbean, sums up the situation:

Caribbean sugar changed the way the world ate, and created untold wealth for plantation owners. The trade was larger and more exploitative than anything that had come before. Sugar money would pay for the Dutch masters’ paintings and build mighty mansions in Bristol. But sugar has no value to the human body. What was really being produced in the Caribbean was luxury.

The luxury produced in places like Antigua is now mostly related to the tourism industry, which has replaced sugar production: lovely paradise holidays and privatised beaches that locals don’t really get a look in on. (Don’t forget, for many, ‘paradise’ equals = no people if you can help it.) Jamaica Kincaid, writing in the late-80s:

Every native would like to find a way out, every native would like a rest, every native would like a tour… [but] they are too poor to live properly in the place where they live, which is the place you, the tourist, want to go – so when the natives see you, the tourist, they envy you, they envy your ability to leave your own banality and boredom, they envy your ability to turn their own banality and boredom into a source of pleasure for yourself.

A Small Place, Jamaica Kincaid

Coming to Antigua as a foreigner I felt a huge self-consciousness related to this idea that as tourists, we are wielding our wealth to enjoy a paradise that maybe local inhabitants would like to enjoy free of (foreign) people. I also felt a self-consciousness of the weight of the colonial past. In Martinique, people talked about békés (the white descendants of the old colonial power) with a spit. Jamaica Kincaid (admittedly heavily criticised for her ‘aggressive’ stance in the book, and reportedly banned from Antigua for 5 years after its publication) had this to say about the ‘bad-minded English who used to rule over Antigua’:

But the English have become such a pitiful lot these days, with hardly any idea what to do with themselves now that they no longer have one quarter of the earth’s human population bowing and scraping before them. They don’t seem to know that this empire business was all wrong and they should, at least, be wearing sackcloth and ashes in token penance of the wrongs committed, the irrevocableness of their bad deeds, for no natural disaster imaginable could equal the harm they did.

The futility of wanting to blend in on the bus, confusion over my interaction with Timothy, my run-in with Mr Yacht Club and the other British I met (who had this aura of people who were once important but weren’t really any more – the leftovers of my grandmother’s era of people), my grandfather’s distant link to one of the principle Big Evils* of the whole colonial period – all speak to this general uneasiness I felt about this dual identity I had here (tourist and colonial descendant). I was getting a bit bogged down. Better to remind myself of the identity I valued most in this moment: that brave/mad single-handed sailor who had spent 3 years trying to scrape together the skills to get here in her own boat without much in the way of prior experience and who had, most importantly, not killed herself along the way.

* Although Nick also notes on the website (linked above) that Gunthorpes, as a centralised sugar refinery, was the thing that started to improve conditions for the descendents of former slaves (who up until this point had barely been able to earn enough money to survive), with higher wages and the opportunity for the development of skills.